SA46. LAND VALUE TAX: A VIABLE ALTERNATIVE By Henry Law

LAND VALUE TAX: A VIABLE TAX ALTERNATIVE?

HENRY LAW, LAND VALUE TAXATION CAMPAIGN

Land value tax (LVT) has been high on the political agenda for most of the past two centuries; in the three decades up to World War I it was backed by a widespread popular movement. Thus, in the broader perspective, its eclipse since about 1950 is exceptional. The flurry of fresh interest in recent years is due, amongst other things, to the

realisation that tax systems have hit the limit to what they can raise, whilst expectations of government continue growing and attempts to cut large welfare bills consistently fail.

LVT in its classic form is a tax on the annual rental value of all land, ignoring buildings and other developments, the valuation being on the assumption that the land is at its optimum use. It would not be additional to existing taxes but a partial or complete replacement for them. Proponents argue that it is a precondition for the solution of a wide range of apparently intractable economic ills. Opponents usually come up with objections

which are criticisms of what is not actually being proposed.

Because LVT is grounded in the fundamental ethical and philosophical issues associated

with property rights, a vastly bigger subject than can be accommodated here, this article

will confine itself to the economic rationale and mechanics of LVT and trace its likely

effects.

1. WHAT IS LAND VALUE?

When talking about land value, what do we mean? Land costs nothing to produce so why

does it have a value at all? Amongst the first to analyse this was David Ricardo, who

formulated the Law of Rent linked to his name. Ricardo used wheat farming as a model,

but we might find it easier to understand the concept by taking the example of a busker on

the London Underground. Given reasonable competence, buskers’ earnings will depend

on where they play. These days, busking is regulated, but what if it were not? The first

busker to arrive would go to the most lucrative spot at the busiest station – Victoria – and

perhaps collect £30 in an hour. The next busker would have to settle for second-best, say

Tottenham Court Road, and take £25. And so on – at Euston and South Kensington a

busker could pick up £20, at Stratford £15, at Wembley £10, at Warwick Avenue £5, and

at Kew Gardens £10 but only on Saturdays and Sundays in good weather. At stations like

Gants Hill in the outer suburbs they might collect just a pound or two. If this sounds like

the Monopoly game, it is meant to. Originally called “The Landlords’ Game”, Monopoly

was invented to demonstrate the same point.

This model acknowledges that there is a minimum level of earnings, below which buskers

will not consider it worth their time and effort to busk. Whilst this is to some extent

subjective, the model is determined by what else they could be doing instead of busking. At

a guess, it is probably around £10 an hour these days, at somewhere like “Wembley”. That,

according to Ricardo’s Law, is the “marginal site”. Buskers would not bother with

anywhere below the margin – under the dotted line in the table. Margins are important

because they are where key economics decisions are made – Warwick Avenue, a quiet

station on the Bakerloo, is not worth bothering with. The plum spot at Victoria gives the

occupant £20 an hour more than could be picked up at Wembley. This is known in

classical economics as “economic rent of land”. It is a bonus due to the advantages of the

site itself, arising because there is a concentration of people at the best locations, where

routes converge.

LVT in its classic form is a tax on the annual rental value of all land, ignoring buildings and other developments, the valuation being on the assumption that the land is at its optimum use.

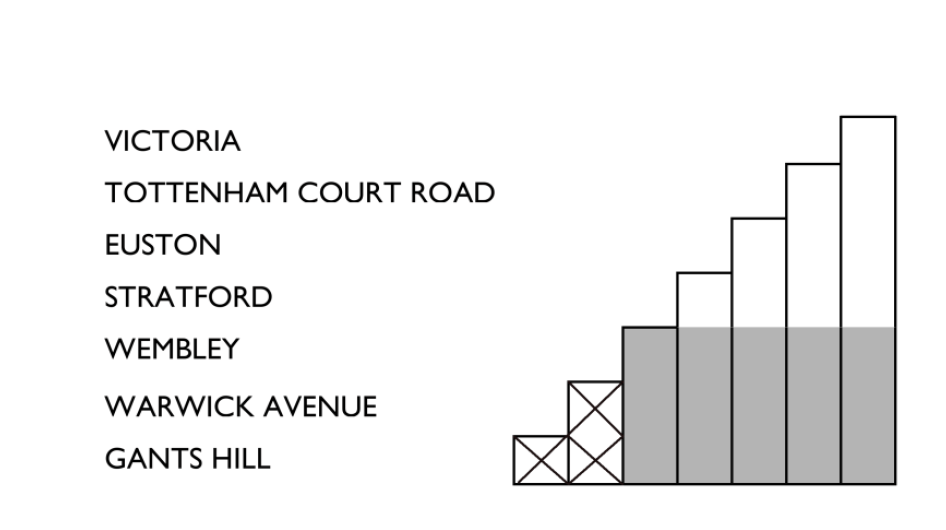

The areas left white in the diagram represent rents, the grey area represents the wages

earned by the buskers, and the sites marked with an X are not viable.

If an additional route was built which brought more traffic to Victoria, the advantage

would be even greater. Conversely, if the new line drew traffic away from Victoria, the

takings there would drop and somewhere else would become the top spot.

Such is the advantage of the best locations that a means must be found for allocating them.

People might come to some informal agreement, or have a fight, or there might be a

protection racket running, in which case the mafiosi could get away with relieving the

musicians of the best part of the rental value.

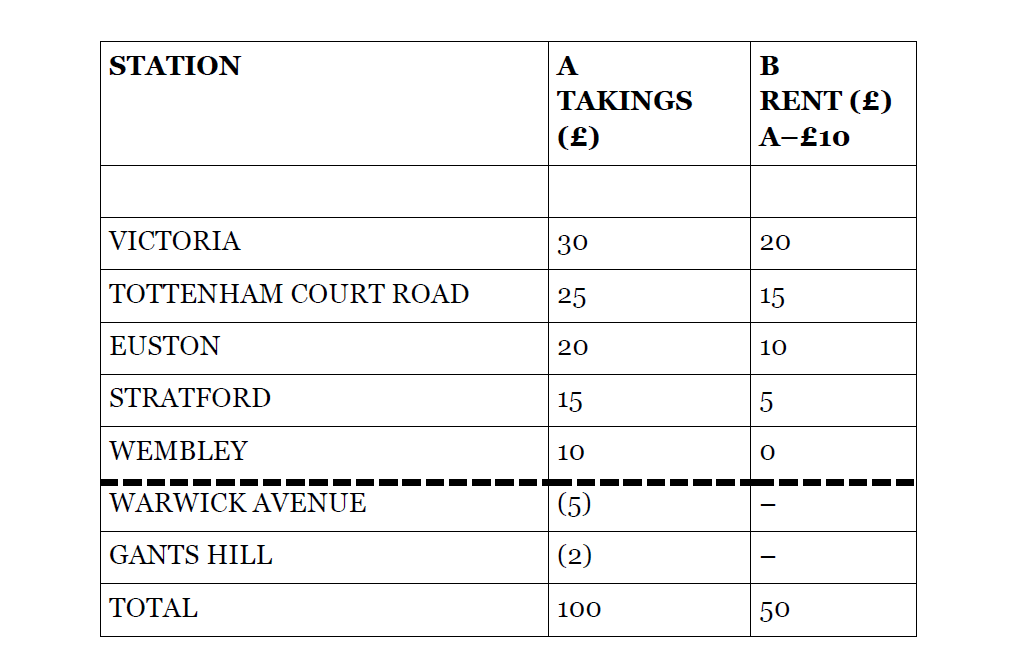

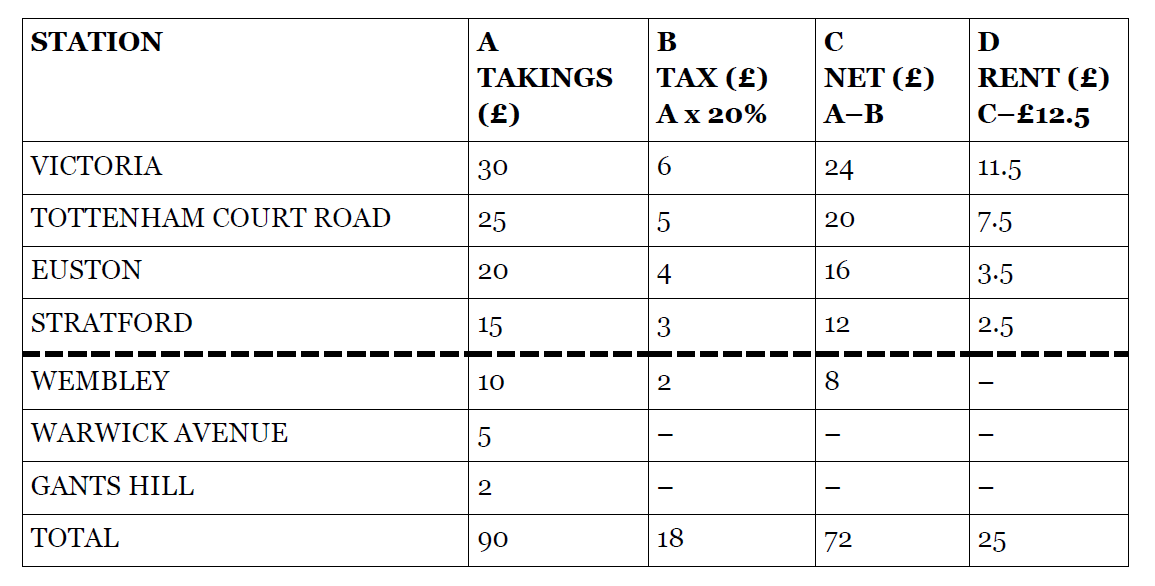

What if the authorities, London Underground, had noticed that here was a useful

additional source of revenue and set up a system of revenue-sharing, on the basis of

“ability to pay”, by levying an “income tax” on the buskers? If the buskers had to pay, say

20% of their takings, things would then be as reflected in the next table.

Busking at Wembley is no longer viable because the busker ends up with only £8. The

margin has now been raised to locations where the takings are at least £12.5 before “tax”.

Sites which would have been viable in the absence of the tax are now below the margin of

viability.

The tax has destroyed work opportunities. There is an overall loss in production. Tax has

cut into both aggregate takings and aggregate rental values. This is called a “deadweight

loss”. The “income tax” does not address problems of allocation; possible protection

rackets remain because rent is still retained by the occupants of the viable sites. The

system would be troublesome to run: the authorities would have to check how much each

busker collected. People could cheat. It would also be unfair, since it would punish the

better players.

This is a model for most contemporary tax systems where the tax is a proportion of income

or profit. Marginal sites are knocked out of use because the potential for productive

activity is below the threshold of viability. The same picture is repeated at a national scale.

This is why regional imbalance in national economies is so intractable. The natural

disadvantages of Scotland and Cornwall are amplified by the tax system. The same applies

in most countries. In this way the economies suffer from a deadweight loss due to the

taxation of wages and profits. The taxation of goods and services has the same effect. This

is one of the reasons why existing tax systems are stretched to the limit.

To summarise: equal amounts of labour and capital do not result in the production of

equal amounts of added value. Differentials due to location give rise to rental values. More

can be earned for the same effort at the most advantageous locations, and so people will

pay a premium to use them, known as economic rent of land.

Land rental value is not the same thing as land price. The two are related, but people

generally equate land value with its price – what someone is willing to pay for it – without

realising that land price is a derivative value. When one buys land, one is purchasing the

stream of rental income from that land, just as one would buy an annuity. The revenue

stream goes with the land title. That price depends on factors like the interest rate, future

There is a real economic loss, with taxpayers being burdened with the cost of welfare.

expectations of income and other speculative considerations such as the possibility of

building houses on agricultural land, or perhaps the chance of new infrastructure – a

motorway or railway – in the vicinity. The purchase of a land title is always a gamble. It is

not a one-way bet. If, for instance, the taxpayer stops looking after the infrastructure or

the economy changes in significant ways, it can be a losing bet.

II. MORE DEADWEIGHT LOSSES

Before moving on to LVT, we need to take note of other deadweight losses due to the socalled “tax wedge” – the difference between the real purchasing power of net wages and

the gross labour cost to employers. To purchase £100 of goods one needs about £120 in

one’s pocket to cover VAT and other taxes on goods and services. To earn that amount in

net pay, the employer incurs a gross labour cost of around £190 – the difference consisting

of income tax and National Insurance charges nominally paid by the employee, and the

employer’s National Insurance contribution. It is a barrier against employment. Some

people, school-leavers, immigrants and people with low skills, are unable to produce

sufficiently to leave them with an acceptable wage. They are caught in the benefits trap.

Unskilled work that they might have done is either not done at all, or employers replace

labour by expensive capital. This is why services like cleaning and care work are pared to

the bone, whilst supermarkets have introduced self-scanning. There is a real economic loss, with taxpayers being burdened with the cost of welfare.

III. WHAT IS LVT?

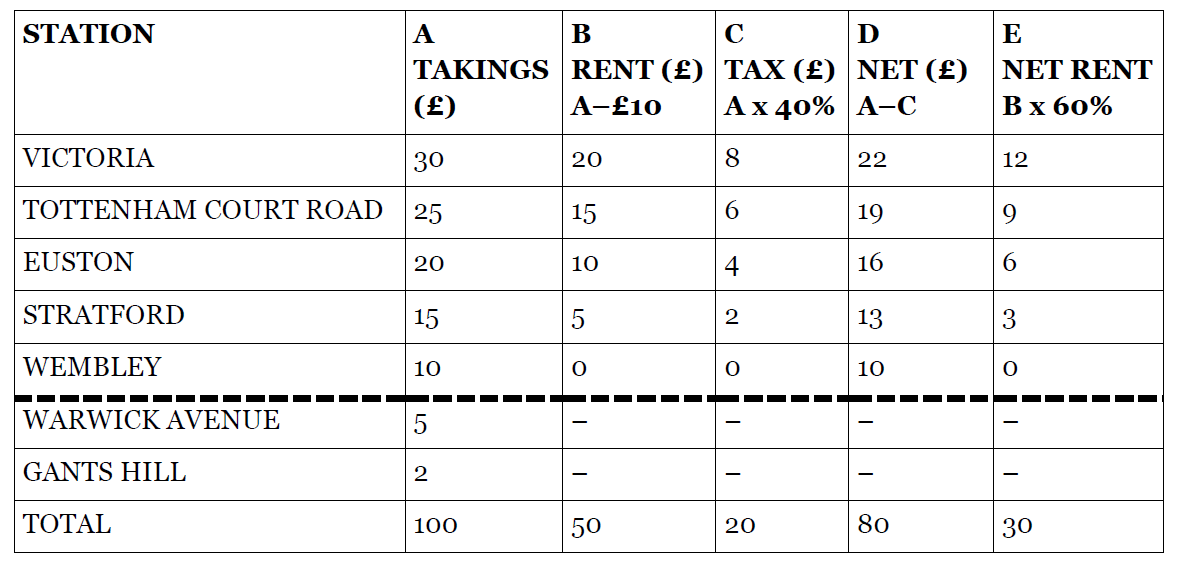

In the case of our buskers, LVT would be the equivalent of making a charge for each site

according to a tariff, based on the rental value. The buskers would buy a permit for a

busking session. The value could soon be established by testing the market. It would be

easier and fairer than collecting a share of the takings. That would be the end of the matter, as the amount the buskers took would be of no concern to anyone. In practice, the easiest thing to do would be to charge the full rental value, leaving everyone with the same

amount as they could have made at the marginal site. Rent is an equaliser. For the sake of

illustration, however, if the charge were levied at a rate of 40% of the rental value, and

since nothing could now be charged for the use of “Wembley”, the end result would look

like this.

Too much should not be read into these figures but the aggregate take is the same as it

would have been in the absence of the tax, because the marginal sites remain viable. The

amount of “tax” collected in this example is about the same as under the income tax

system discussed earlier, whilst aggregate pre-tax rental values have gone up by roughly

the amount of “income tax” that no longer has to be paid. Busking remains viable on any

pitch where £10 can be earned, eg “Wembley”. The margin stays where it would be in the

absence of any tax. Sites close to the margin are not knocked out by the tax.

Disadvantages of location are not amplified as they are by taxes on incomes or profits, so

the number of sites of opportunity is optimised. Aggregate rental values are unaffected,

since what is happening is a sharing of rental values between London Underground and

the buskers. The tax does not cut into its own base. Thus a tax on rent is an exception to

the Laffer rule; the yield is proportional to the tax all the way up to 100% ie when the full

rental value is charged. This is of course exactly what, as landlord, London Underground

does when it leases kiosks on its premises to newsagents and retailers. There is no

shortage of tenants.

Before leaving our musicians, there is one further point to be made: LVT is not really a tax

at all. Land Value Taxation is a misnomer. It is functionally equivalent to a national land

rent charge, where the taxpayers pay for what they get, and get what they pay for.

IV. LVT IN PRACTICE

Administratively, LVT works in a similar way to the UK’s national business rate, the only

difference being that all land is registered and assessed, and buildings and improvements

on the site are ignored. This simplifies the system. A rate of tax is set and owners of the

land are billed, just as business occupiers are billed today.

V. VALUATION

Objectors argue that valuation of sites is difficult. Yet professionals do it all the time.

When a valuer says that house A is worth a certain amount, whereas an identical house B

in a different location is worth more, the valuer is assessing the relative site values. When aproperty comes on the market for major redevelopment, it will be valued as a site, minus

the costs of demolition and clearance. Pilot-scale surveys have confirmed that the

establishment of site rental values for LVT purposes would present no special difficulties.

These days, property websites used both by estate agents and the public mean that anyone

who wants to know can work out property site values.

Under a system of land value taxation, valuers assume that the site is developed to its

maximum extent consistent with the planning regulations. In most circumstances it would

The aim of LVT is to replace, initially, existing property taxes,

and to allow the phasing-out of other damaging taxes.

be existing use value, but if the property was allowed to become derelict or demolished,

the owner would remain liable for the land value tax, in contrast to what happens with the

present property taxes. Because third-party planning applications can be made, for example, by local authorities, owners of land that was ripe for development, such as urban

fringe, would not be able to play the market by withholding it.

For an LVT system to function openly and effectively, the register and valuations must be

available to the public, and revaluations must be frequent – certainly at not more than

five-yearly intervals. With modern Geographical Information Systems, annual revisions

become feasible.

VI. NATIONAL OR LOCAL?

Technically, LVT is suitable for all tiers of government because a system of precepting can

be used. In practice however, because of the variation in aggregate land values between

different local authorities, LVT should be a uniform national tax; at a given percentage

rate of tax, many times more revenue can be raised in Kensington than in Kendal. This is,

however, true of any tax – the same applies to a local income tax or a local sales tax. It is

why local taxation in any shape or form tends to be a political minefield.

VII. THE BENEFITS

The aim of LVT is to replace, initially, existing property taxes, and to allow the phasing-out

of other damaging taxes. Because, as shown earlier, existing taxes cut into land values,

those land values rise as present taxes are cut. This is why it is impossible to answer a

question that is often posed – “how much can LVT raise?” It depends on what other taxes

are removed. Broadly speaking, aggregate land value increases on a £1 for £1 basis as other

taxes are cut. Assuming that LVT is sufficiently high, the benefits include:

- Reduction of deadweight losses and associated poverty and unemployment.

- Discouragement of land speculation – LVT must be paid whether land is in use or

not. Buying property or land, and leaving it empty or undeveloped, becomes

unprofitable, as does the under-use of valuable sites. - Minimal administration costs.

- No avoidance and evasion. Land cannot be hidden or removed to a tax haven.

- Credit-fuelled boom-slump cycles curbed. LVT knocks the speculative element

out of land pricing and by acting as a negative feedback loop, prevents the

development of price bubbles. - Land value tax cannot be passed on. Rents settle at the maximum that can be

obtained. Landlords cannot raise them on account of a land value tax – on the

contrary – the competition between them is sharper and they must accept the best price they can to keep their property occupied and maintain their revenue

from which to pay the tax.

VIII. WHY HASN’T LVT BEEN TRIED?

Actually it has, and remains in operation, though usually at a low level and as a local tax.

Examples are Singapore, Taiwan, Australia, parts of the USA and Scandinavia. LVT is an

important factor in the success of the economies of the first two. To the extent that they

are set up on sound principles, ie based on annual rental values with frequent revaluations,

they run smoothly and efficiently. Many countries already have a property tax of some

kind and in these cases the existing system can be adapted, since land value taxation is a

simplification of existing taxes levied on land plus buildings.

IX. WHAT IS THE DIFFICULTY?

The biggest difficulty in getting LVT accepted and implemented is that there are vested

interests in keeping things the way they are. Home owners enjoy the rental stream from

their own properties as an imputed income, and they cherish the prospect of the windfall

gains which they can enjoy. More significantly, the entire system of banking and finance is

constructed on the appropriation of land rental value by private individuals and

companies. Some people do nicely, and behind them is an army of others who aspire to do

the same thing. Many seem to be attached to the psychological comfort of land ownership

and find the notion of a tax threatening, whilst ignoring the prospect of tax-free earnings

and tax-free goods in the shops which would be possible if LVT substantially replaced

existing taxes. As pointed out at the beginning of this piece, there are ethical and

philosophical issues associated with property rights. Until these are recognised and

attitudes change, LVT is not going to come easily.

HENRY LAW has pursued a diverse career. After graduating in Chemistry at Lincoln College, Oxford in 1963, he worked for a time as a science teacher, before following up a long-standing interest in architecture, town planning and landscape design, obtaining a qualification in the latter subject at Newcastle University. He subsequently worked within that field until 1991, as a local authority planning officer and freelance journalist. His interest in land taxation arose through an awareness of the link between the tax system and seemingly intractable problems of land use policy. He currently lives in Sweden, having moved there several years ago.

Articles

Land Value Tax Links

The Tax Burden

Article List

- Welcome

- SA 88. Is there another way? by Tommas Graves

- SA 87. Time for a look at Rent by Tommas Graves

- SA 86. It’s rather Odd………….. By Tommas Graves

- SA85. Born to become a Georgist by Ole Lefmann

- SA84. Happy Nation by Lasse Anderson

- SA83. Ulm is buying up land, sent by Dirk Lohr

- SA82. Radical Tax Reform by Duncan Pickard

- SA 81. All taxes come out of Rents, by Rumplestatskin.

- SA 80. The Housing Crisis and the Common Good, by Joseph Milne

- SA 79. The “housing crisis” is no such thing, by Mark Wadsworth

- SA78. The Inquisitive Boy by “Spokeshave”

- SA 75. A Note on Swedish Taxes, by Tony Vickers MScIS MRICS

- SA 74. Homes Vic by Emily Sims

- SA73 Public Revenue Without Taxation by Peter Bowman

- SA71. Two presentations by Ed Dodson

- Short Sighted Benevolence

- SA 72. CAN YOU SEE THE CAT?

- SA70. Dissertation on Land Rental by Marion Ray

- Verses on the theme

- SA69. Argentina by Fernando Scornic Gerstein

- SA68. The Right to Work, by Leslie Blake

- SA66. The Most Wonderful Manuscript by Ivy Akeroyd 1932

- SA65. Housing Crisis? What Housing Crisis? by Mark Wadsworth

- SA64. Making Use of History by Roy Douglas

- SA63. The Fairhope Single Tax Colony – from their website

- TP35. What to do about “The just about managing” by Tommas Graves

- SA62. A Huge Extra Resource, by Ed Dodson

- SA61. Foundations of Earth Sharing Why It Matters: By Lawrence Bosek

- SA60. How to Restore Economic Growth, by Fred Foldvary, Ph.D.

- Two cartoons by Andrew MacLaren MP

- SA59. The Meaning of Work, by Joseph Milne

- SA 58. THE FUNCTION OF ECONOMICS, by Leon Maclaren

- SA 57. CONFUSIONS CONCERNING MONEY AND LAND by Shirley-Anne Hardy

- SA 56. AN INTRODUCTION TO CRAZY TAXATION – by Tommas Graves

- SA 55. LAND REFORM IN TAIWAN by Chen Cheng (preface) 1961

- SA54. Saving the Commons in an age of Plunder – by Bill Batt

- SA53.- Eurofail – VAT, by Henry Law

- SA52. Low Hanging Fruit – by Henry Law

- SA51. Location Theory and the European Union, – by Peter Holland

- SA50. Finland’s Basic Income – why it matters by Fred Foldvary, Ph.D.

- SA 29. A New Model of the Economy, by Brian Hodgkinson, as reviewed by Martin Adams of Progress.org

- Economics Explained (In 1 Simple Cartoon)

- SA 48. LANDED (Freeman’s Wood) by John Angus-StoreyG2

- SA 47. Justice and the Common Good by Joseph Milne

- SA 49.Prosper Australia – Vacancies Report

- SA39. A lesson from Alaska: further thoughts? By Alanna Hartzog

- SA23. Taxation: a brief history by Roy Douglas

- SA45. Of course, it wouldn’t solve all problems………by Tommas Graves

- SA43. TIME TO CALL THE LANDOWNERS’ BLUFF by Duncan Pickard

- SA44. Answering questions to UN Habitat 3 Financing Urban Development by Alanna Hartzog

- SA15. Why we don’t have a Housing Shortage, by Ben Weenen

- SA27. Money and Natural Law, By Tommas Graves

- SA42. NO DEBT, HIGH GROWTH, LOW TAX By Andrew Purves

- SA40. High Land Prices and Rural Unemployment, by Duncan Pickard

- SA28. Economics is a Natural Science by Duncan Pickard

- SA34. Economic Answers to Ecological Problems by Seymour Rauch

- SA22. Public Revenue without Taxation by David Triggs

- SA41. WHAT FAMOUS PEOPLE SAID ABOUT LAND contributed by Frank de Jong

- SA36. TAX THE RICH? Pikety and all that……..by Tommas Graves

- SA46. LAND VALUE TAX: A VIABLE ALTERNATIVE By Henry Law

- SA35. HOW CAN THE ECONOMY WORK FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL? By Peter Bowman, lecture given at the School of Economic Science.

- SA38. WHO CARES ABOUT THE FAMILY by Ann Fennell.

- SA30. The Turning Tide: The Beginning of Monetary Trade in Anglo-Saxon England by Raymond Makewell

- SA31. FAULTS IN THE UK TAX SYSTEM

- SA33. HISTORY OF PUBLIC REVENUE WITHOUT TAXATION by John de Val

- SA32. Denmark By Ole Lefman

- SA25. Anglo-Saxon Land Tenure by Raymond Makewell

- SA21. China – Four Thousand Years of Taxing the Land by Peter Bowman

- SA26. The Economic Philosophy of Georgism, by Emma Crosby